What is Osteosarcoma?

Osteosarcoma (OS) is the most common primary bone tumor found in dogs. It accounts for up to 85% of all malignancies originating in the skeleton. It mostly occurs in middle-aged to older dogs, with a median age of 7 years. Primary rib OS tends to occur in younger adult dogs with a median age of 4.5 to 5.4 years.

What makes a dog more likely to get osteosarcoma?

Larger breeds have a high propensity for the disease. Dogs like Great Danes, Irish Setters, Doberman Pinschers, Rottweilers, German Shepherds, and Golden Retrievers are at greater risk of contracting osteosarcoma because of their size and weight. Intact males and females are also highly predisposed.

Where in the dog’s body does osteosarcoma occur?

Osteosarcoma can occur in any bone but the limbs account for 75%-85% of all affected bones and is called ‘appendicular osteosarcoma’. The remaining affects the axial skeleton comprising the maxilla, mandible, spine, cranium, ribs, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and pelvis.

Osteosarcoma of extraskeletal sites is rare, but primary OS has been reported in mammary tissue, subcutaneous tissue, spleen, bowel, liver, kidney, testicle, vagina, eye, gastric, ligament, synovium, meninges, and adrenal gland. It develops deep within the bone and can become excruciatingly painful as it grows outward and the bone is destroyed from the inside.

What causes Canine Osteosarcoma?

The exact causes of osteosarcoma are not known. But factors like ionizing radiation, chemical carcinogens, foreign bodies, (including metal implants, like internal fixators, bullets, and bone transplants), and pre-existing skeletal anomalies like the site of healed fractures sometimes lead to osteosarcoma.

It has also been associated with chronic osteomyelitis and in fractures in which no internal repair was used. Osteosarcoma has been concurrently seen in dogs with bone infarcts. In dogs, injected with plutonium during experimental studies, the occurrence has been found to be rampant.

What are the genetic factors that can induce osteosarcoma tumor growth?

Genetic factors are also believed to induce the development of tumors. Dogs with OSA have been found to have aberrations of the p53 tumor suppressor gene. In laboratory animals, both DNA viruses (polyomavirus and SV-40 virus) and RNA viruses (type C retroviruses) have been found to trigger osteosarcoma. Alterations in several growth factors like cytokine or hormone signaling systems have been documented in the pathogenesis of the disease. Greater blood vessel density has been shown to be an indicator of primary Osteosarcoma with metastasis.

What are the symptoms of canine osteosarcoma?

The most typical symptoms for osteosarcoma are when dogs display distinctive lameness and there is also swelling at the primary site. In some cases, there might be a history of mild trauma before the onset of lameness. There is visible pain due to microfractures or disruption of the periosteum. The dog might also be susceptible to frequent fractures.

Are the symptoms different on different parts of the dog’s body?

The signs associated with the axial skeletal OS are site dependent. They vary from localized swelling with or without lameness to dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing) exophthalmos (bulging of the eye anteriority out of the orbit) and pain on opening of the mouth (caudal mandibular or orbital sites), facial deformity, and nasal discharge and hyperesthesia (is a condition that involves an abnormal increase in sensitivity to stimuli of the senses) with or without neurological symptoms. The pain can cause other problems like irritability, aggression, loss of appetite, weight loss, whimpering, sleeplessness, and reluctance to exercise.

What diagnostics are used to determine treatment for osteosarcoma in dogs?

Because OS treatment is so dependent on understanding your dog’s exact issues and progression of the bone cancer, your veterinarian may advise several procedures to determine the best treatment plan. These include but aren’t limited to:

Radiographic projections – The first step is to take lateral and craniocaudal radiographic projections. Special views may be crucial for tumors occurring in sites other than in the appendicular skeletons.

Rectal exam – A rectal exam is also very important with special attention paid to the genitourinary system to help rule out the presence of a primary tumor.

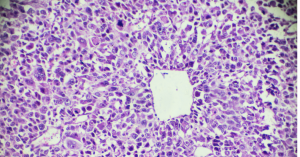

Biopsy – A biopsy is also mandatory because, in the initial stages, the tumor cells are not distinctly visible. Another reason could be fungal bone infections that also show symptoms similar to osteosarcoma. Bone biopsy may be performed as an open incisional, closed needle, or trephine biopsy. The advantage of the open technique is that a large sample can be procured which makes histopathological diagnosis more accurate.

Biopsy – A biopsy is also mandatory because, in the initial stages, the tumor cells are not distinctly visible. Another reason could be fungal bone infections that also show symptoms similar to osteosarcoma. Bone biopsy may be performed as an open incisional, closed needle, or trephine biopsy. The advantage of the open technique is that a large sample can be procured which makes histopathological diagnosis more accurate.

Fine needle cytology – It is very important to understand how far the disease has metastasized. Therefore, fine needle cytology is performed on any enlarged node to determine the extent of the spread of the ailment. Sites of bone metastasis may be detected by a careful orthopedic examination with palpation of long bones and the accessible axial skeleton.

Thoracic auscultation – Organomegaly (abnormal enlargement of organs) may be detected by abdominal palpation. Thoracic auscultation is important to detect intercurrent cardiopulmonary disorders. Advanced imaging, like (CT, MRI, and PET/CT) may play a role in patient staging and is used to evaluate for pulmonary metastases and for tumor vascularity (low body fat, high blood pressure, and muscle engorgement).

Radiology – Bone survey radiography has been beneficial in detecting dogs with second skeletal sites of osteosarcoma. A nuclear bone scan can be a useful tool for the detection and localization of bone metastasis in dogs. Any region of osteoblastic activity will be identified by this technique including osteoarthritis and infection.

What treatments for osteosarcoma are available for dogs?

Amputation

Removal of the affected limb is the standard local treatment for canine appendicular osteosarcoma. A complete forequarter amputation for forelimb lesions is generally recommended, as in a coxofemoral disarticulation amputation for hind leg lesions. Amputation results in the total removal of the disease. For proximal femoral lesions, a complete amputation and en bloc acetabulectomy (excision of the hip ball and socket joint) is recommended.

Limb-sparing surgery

A limb-sparing surgery is a procedure that replaces a diseased bone and reconstructs a functional limb by using a metal implant, a bone graft from another dog (allograft), or a combination of bone graft and metal implant (alloy prosthetic composite). Most dogs perform well with an amputation but in certain instances where the dog suffers from severe pre-existing neurological and orthopedic diseases, limb-sparing is preferred over amputation.

Probable candidates for limb-sparing surgery are dogs that have primary tumors confined only to the bone and are in otherwise good general health. Other factors include an absence of pathologic fracture, less than 360-degree involvement of soft tissues, and firm soft tissue mass versus an edematous (An excessive accumulation of serous fluid in tissue spaces or a body cavity) lesion. The most suitable cases of limb-sparing are dogs with tumors in the distal radius or ulna (front leg at the “wrist”). In all cases, cephalosporin antibiotics are administered intravenously before, during, and after the operation.

These various methods of limb-sparing surgery are cortical allografts, pasteurized or irradiated autografts, ulna transposition autografts, and stereotactic.

An allograft is sterile, the frozen bone that is stored in a bone bank. In autograft, the tumor site is removed from the leg and then treated with a high dose of radiation to “kill” the tumor. Once the allograft, autograft, or metal implant is inserted into the hollow, a stainless steel plate is applied, and the wrist is fused. The plate remains there unless it creates problems. Although the dog cannot bend the wrist, this is not painful and dogs can use the leg almost normally. In some cases, dogs with tumors of the ulna may not require an allograft or fusion of the wrist.

The surgery takes about 2 to 3 hours. But dogs stay in the hospital for 2-4 days. After surgery, a soft padded bandage (usually not a cast or splint) is applied to the leg. Weight-bearing and range-of-motion exercises can be started immediately after surgery. It is important to prevent contractures of the toes and to decrease swelling in the limb. Most dogs resume normal activities within one to two months after surgery. Medications that are routinely used after surgery include antibiotics and pain medications.

The complications that might arise after limb-sparing surgery could be implant failure, local tumor recurrence, and infection. Implant failure occurs in approximately 10% of cases. The use of an orthopedic cement known as methylmethacrylate reduces the incidence of screw loosening, implant failure, and fracture. Local tumor recurrence is caused by incomplete resection or, more commonly, residual neoplastic cells in the soft tissue adjacent to the tumor capsule after marginal resection of the primary bone tumor.

Infection is another significant postoperative complication. Though the cause of infection is unknown, extensive resection of soft tissues, poor soft tissue coverage, use of orthopedic implants, and administration of local and systemic chemotherapy are thought to be the contributing factors. It has been observed that antibiotic-impregnated cement minimizes the risk of infection considerably. If the infection recurs despite treatment, antibiotic-impregnated methylmethacrylate beads can be surgically implanted adjacent to the infected bone. In these cases, amputation may be needed as a salvage procedure.

There is very little chance that the tumor will recur in the leg. At the time of operation, an absorbable chemotherapy (cisplatin) sponge is inserted into the wound. This reduces the chances of local recurrence. The sponge is a biodegradable polymer, which slowly breaks down in the body, releasing cisplatin in very high concentrations to the tissues in the surgery site. Only a low dose of cisplatin gets into the bloodstream. This high local dose of cisplatin will kill cancer cells remaining in the leg after limb-sparing surgery.

Osteosarcoma Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy begins 2 weeks after surgery. The drugs administered are cisplatin, carboplatin, or doxorubicin. The standard protocol is 4 to 6 treatments, 3 weeks apart. After the surgery, chemotherapy is recommended to catch any stray cancer cells that may have already traveled through the blood to other areas. In the wake of no chemotherapy, there is very little chance that your dog will survive one year after surgery.

Periodic follow-up is necessary to monitor the dog’s progress. Radiation doses can be applied to the tumor in 3 doses (the first two doses 1 week apart, the second two doses 2 weeks apart.) Improved limb function is usually evident within the first 3 weeks and typically lasts 4 months. When pain returns, radiation can be re-administered for further pain relief if deemed appropriate based on the stage of cancer at that time.

What is the survival rate for dogs with Osteosarcoma?

The prognosis for patients with OSA depends on several factors. The average survival in dogs with osteosarcoma treated with surgery and chemotherapy is approximately 1 year. The prognosis is very poor for patients below 7 years of age with large tumors in the proximal humerus. Recently, a median survival time of 7 months was reported for dogs receiving radiation therapy along with chemotherapy; whereas a combination of surgery and chemotherapy showed more encouraging median survival rates of 235-366 days with up to 28% surviving two years after diagnosis.

Dogs between 7 and 10 years of age have greater survival rates than younger and older dogs. In axial osteosarcoma, the medial survival rate is 4-5 months because of the reoccurrence of the disease and complete surgery is not possible because of the location.

Thank you for utilizing our Canine Cancer Library. Please help us keep this ever-evolving resource as current and informative as possible with a donation.

Reference

Withrow and MacEwen’s Small Animal Clinical Oncology– Stephen J. Withrow, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology), Director, Animal Cancer Center Stuart Chair In Oncology, University Distinguished Professor, Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado; David M. Vail, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology), Professor of Oncology, Director of Clinical Research, School of Veterinary Medicine University of Wisconsin-Madison Madison, Wisconsin

Other Articles of Interest:

Blog: How To Help Pay For Your Dog Cancer Treatment Cost: 7 Fundraising Ideas

Blog: What Are Good Tumor Margins in Dogs and Why Are They Important?

Blog: Dispelling the Myths and Misconceptions About Canine Cancer Treatment

Blog: Financial Support for Your Dog’s Fight to Beat Cancer

Blog: Cancer Does Not Necessarily Mean A Death Sentence

Blog: What To Do When Your Dog Is Facing A Cancer Diagnosis – Information Overload

Blog: Dog Cancer Warning Signs: Help! I Found a Lump on My Dog

Recent Comments